Scanning Tailscale Funnel

Tailscale is a pretty great VPN-like software. It puts all your devices on a secure Wireguard network in like a minute, so you can be really confident any traffic between any of your devices is end-to-end encrypted.

But I was a bit confused when I recently read about Tailscale’s Funnel feature, which is kind of the opposite of everything else Tailscale does. Instead of making services available only to approved devices inside your Tailscale network, it takes a port from a Tailscale node and exposes it to the whole Internet. To me this seems like quite a dangerous or at least misleading feature.

I think the crux of the matter is that Tailscale has done a really great job selling its value and making it easy for even non-technical users to use. With the Funnel feature, I can easily imagine that less-technical users will believe that the same protections apply to their funneled services (even though that’s obviously wrong to experienced engineers). Unfortunately, there’s really no warning or explanation of the potential dangers of exposing an insecure service. In fact, the examples explicitly suggest directly exposing a fileserver with directory listings from the user’s machine.

Sniping Node Names via Certificate Transparency

The Funnel feature looks generally well-thought-through.

When you expose your service, Tailscale automatically handles the DNS to give you a hostname like node-name.tailnet-name.ts.net.

In fact, Tailscale even uses LetsEncrypt to automatically generate a TLS certificate for you.

But for an attacker interested in scanning and exploiting Tailscale users, this makes it trivial to find the hosts exposed by Tailscale Funnel.

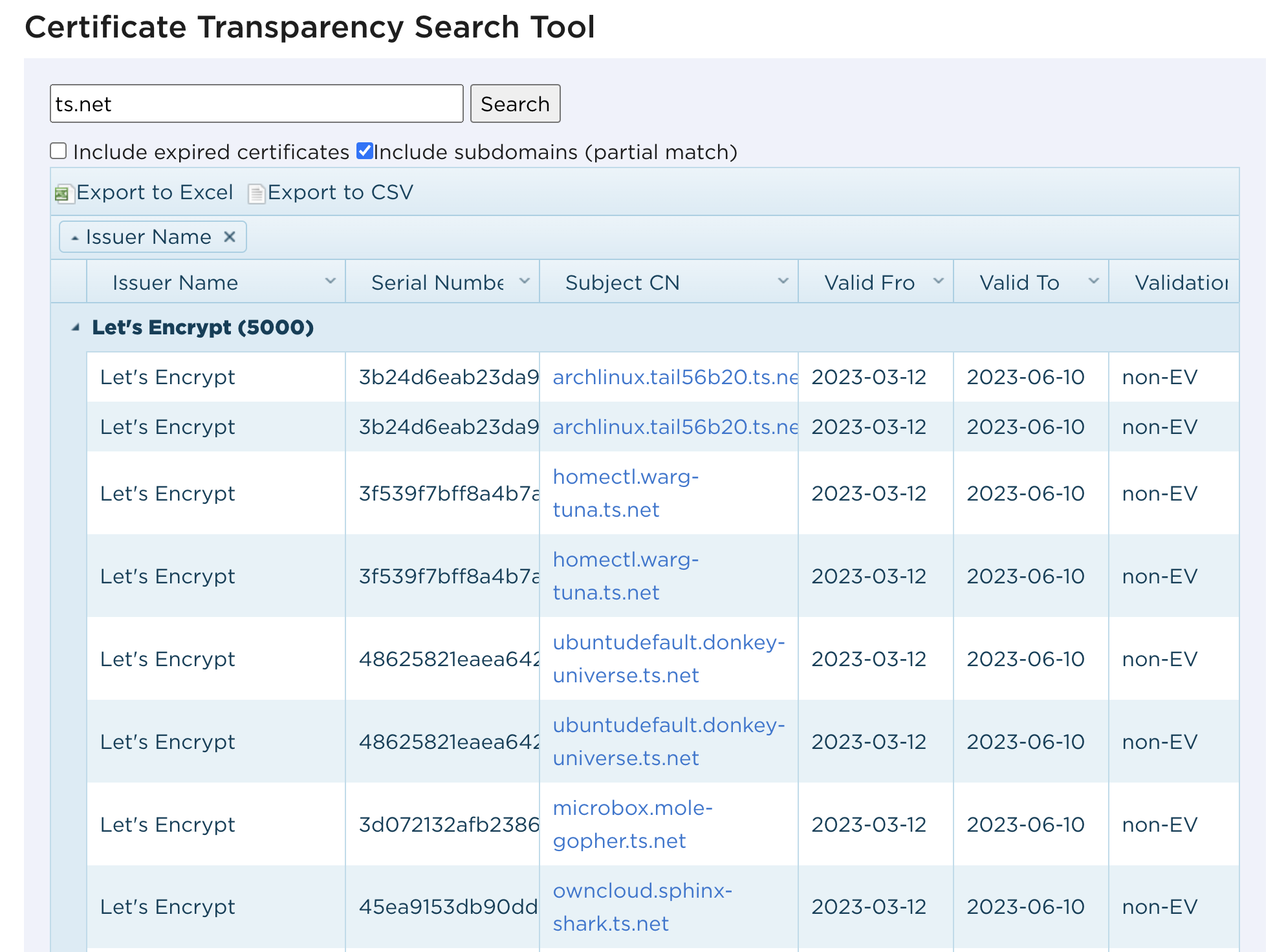

Certificate Transparency is a requirement of all modern CAs that provides a public log of all widely-trusted certificates. There are a variety of search engines which make it easy to search the Certificate Transparency logs. In this case, I used Entrust’s Certificate Transparency Search Tool which returned a list of a few thousand hostnames and gave me a convenient CSV output.

I took this list of hostnames and ran some simple nmap scans to identify live hosts:

nmap -n -iL domains.txt -oA tailscale-funnel -sS -Pn -p 443,8443,10000 -T4

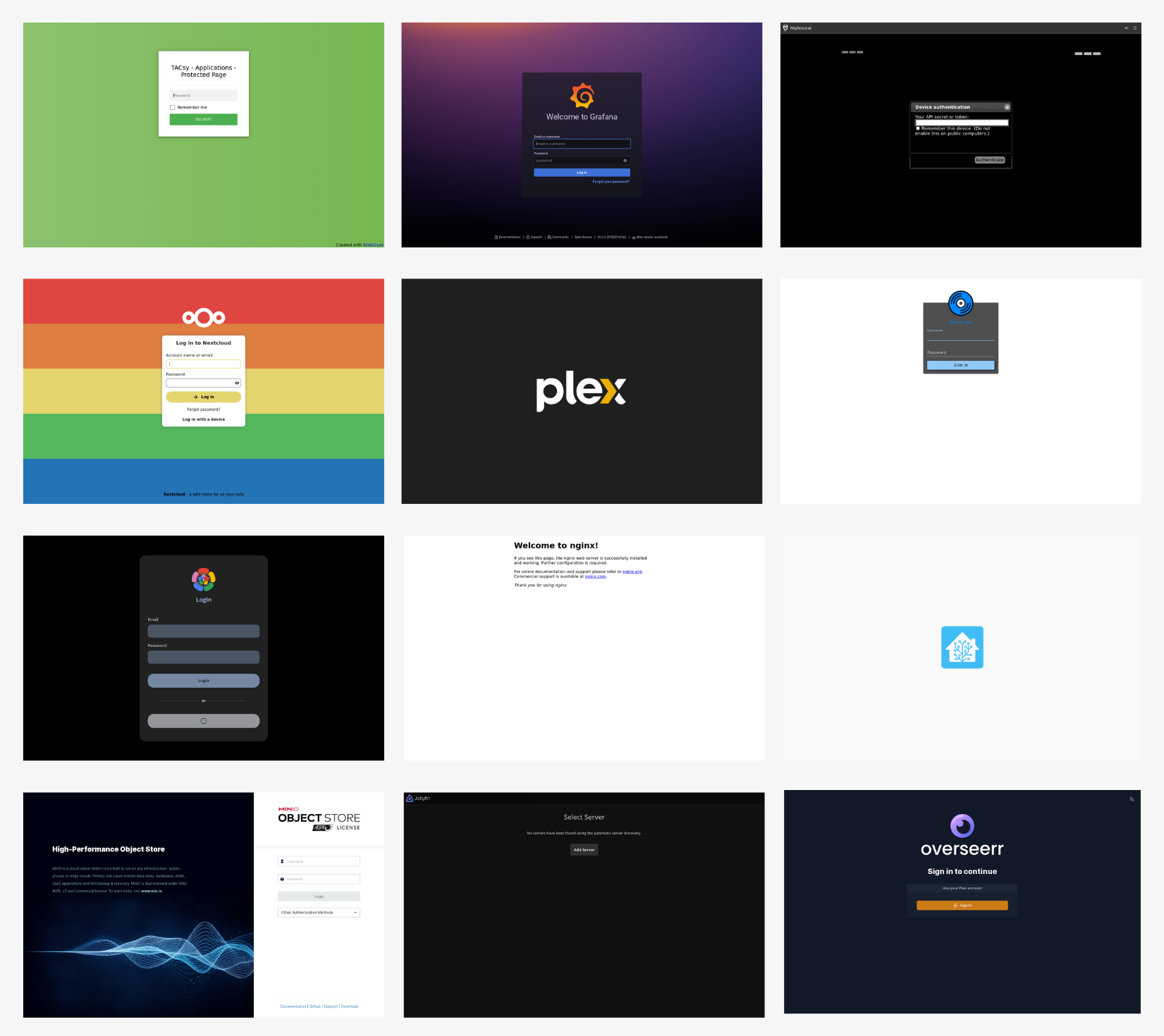

With the list of live hosts, I used the gowitness tool to gather screenshots of each host:

gowitness --fullpage file -f livehosts.txt

It’s about what you’d expect: lots of instances of self-hosted OSS software: primarily HomeAssistant and media-streaming software like Plex and Jellyfin (ref. fun recent vulns). More than a few default nginx instances and generic webservers, including Tomcat. Certainly some items of concern such as directory listings of obviously personal content, and a variety of minimally-configured-looking infrastructure like Jenkins. I didn’t do any deep investigation, but there are absolutely a few things in here that give off strong vibes of “5 minutes to a root shell”.

What would I do different?

First, I would update the documentation to explain the safe and unsafe use cases for the feature. Warnings should really be present in the CLI or UI as well. To go above and beyond, consider a proactive email to users of the feature to notify them to keep their services secure.

It doesn’t seem feasible for Tailscale to add some kind of authentication to this feature without losing a good measure of its usefulness. Requiring a secret token or client certificate would probably not be compatible with most usecases.

What they could do would be to use secret hostnames by default. Right now, the hostnames configured for each funnel are exposed directly in CT logs (though they’re pretty guessable regardless). Instead, Tailscale could go one level deeper and require a random, unguessable subdomain by default. This subdomain would have to be kept out of CT logs, which would mean giving each node a wildcard certificate instead of a normal certificate. Then, Tailscale could reject any connections which don’t connect using the right subdomain - effectively making the subdomain into a secret token.

Using a secret subdomain isn’t a silver bullet solution, since DNS definitely isn’t designed to keep domains secret, but it would very effectively stop casual scanners. And users could still opt in to using a chosen subdomain if they want. As an extra bonus, this solution would allow users to assign different services a unique subdomain, enabling multiple services to listen on the same host.